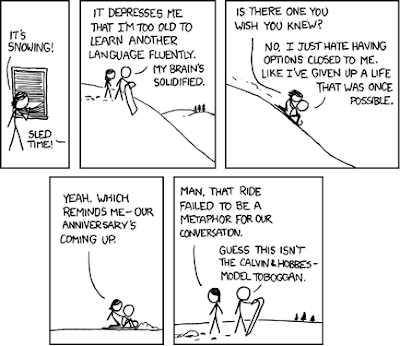

Here's yet another stick-figure comic (for those keeping track, that's four blog posts in a row). This one's about correlation.

Correlation is a tricky concept. We tend to see the world in all-or-nothing terms, rather than in shades of probability.

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Friday, February 26, 2010

Another Snow Day!

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

Our Inductive Minds

Here are some more thoughtful links on inductive reasoning.

- What are the benefits and dangers of generalizations?

- What makes stereotyping illogical?

- Beware: we often make snap judgments before thinking through things. Then when we do think through things, we just wind up rationalizing our snap judgments.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

inductive,

links

Sunday, February 21, 2010

Learning from Experience

Here's some stuff on inductive arguments. First, a video of comedian Lewis Black describing his failure to learn from experience every year around Halloween:

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

There's another stick-figure comic about scientists' efforts to get as big a sample size as they can to improve their arguments.

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

There's another stick-figure comic about scientists' efforts to get as big a sample size as they can to improve their arguments.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

inductive,

links,

videos

Monday, February 15, 2010

Structure

One of the trickier concepts to understand in this course is the structure of an argument. This is a more detailed explanation of the term. If you've been struggling to understand this term, the following might help you.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises, if they were true, would provide good evidence for us to believe that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, you would be able to figure out from those premises alone that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures guarantee that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Deductive Args (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows must be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, MUST the conclusion also be true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths guarantees a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Deductive Args (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – they don’t naturally follow. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting whales take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises, if they were true, would provide good evidence for us to believe that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, you would be able to figure out from those premises alone that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures guarantee that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Deductive Args (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows must be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, MUST the conclusion also be true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths guarantees a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Deductive Args (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – they don’t naturally follow. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting whales take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Evaluating Deductive Arguments

Here are the answers to the handout on evaluating deductive arguments that we went over in class. Perhaps I should have titled the handout "So Many Bad Args!"

1) All kangaroos are marsupials.

All marsupials are mammals.

All kangaroos are mammals.

Sean is a person.

Sean is funny.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

All boring things are taught by Sean

This class is taught by Sean.

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.

All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

All humans are shorter than 10 feet tall.

All students in here are shorter than 10 feet tall.

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

1) All kangaroos are marsupials.

All marsupials are mammals.

All kangaroos are mammals.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- valid

overall - sound

2) (from Stephen Colbert)

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

3) Some people are funny.Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

structure- valid (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean is a person.

Sean is funny.

P1- true (we might disagree over who specifically is funny, but nearly all of us would agree that someone is funny)4) All email forwards are annoying.

P2- true (each "Sean" in this handout refers to your teacher, Sean Landis)

structure- invalid (the 1st premise only says some are funny; Sean could be one of the unfunny people)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)5) All bats are mammals.

P2- true

structure- valid (the premises establish that some email forwards are both annoying and false; so some annoying things [those forwards] are false)

overall - unsound (bad first premise)

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

P1- true6) Some dads have beards.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "All bats are the sorts of creatures who have wings.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living bat has wings," since some bats are born without wings)

structure- invalid (we don't know anything about the relationship between mammals and winged creatures just from the fact that bats belong to each group)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true7) This class is boring.

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective)

structure- valid (if all the people with beards were mean, then the dads with beards would be mean, so some dads would be mean)

overall- unsound (bad 2nd premise)

All boring things are taught by Sean

This class is taught by Sean.

P1-questionable ("boring" is subjective)8) All students in here are mammals.

P2- false (nearly everyone would agree that there are some boring things not associated with Sean)

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- invalid (the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!10) All students in here are humans.

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

structure- valid (same structure as in argument #1, just with an extra premise)

overall- unsound (bad 3rd premise)

All humans are shorter than 10 feet tall.

All students in here are shorter than 10 feet tall.

P1- true11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true!

structure- valid (same structure as arg #1)

overall- sound

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false)12) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)13) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise and structure)

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise)

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)

P2- false

structure- valid (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad premises and structure)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

deductive,

videos

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Quiz You Once, Shame on Me

The first quiz will be held at the beginning of class on Wednesday, February 17th (we're pushing it back one more class because of the snow day). You will have about 25 minutes to take it.

There will be a multiple choice section, a section on evaluating deductive arguments, a section on evaluating arguments, and a section where you provide examples of specific kinds of arguments. Basically, it will look like a mix of the homework and group work we've done in class so far.

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from chapters 6, 8, and part of 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's what will be covered on the quiz:

There will be a multiple choice section, a section on evaluating deductive arguments, a section on evaluating arguments, and a section where you provide examples of specific kinds of arguments. Basically, it will look like a mix of the homework and group work we've done in class so far.

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from chapters 6, 8, and part of 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's what will be covered on the quiz:

- definitions of: logic, reasoning, argument, structure, sound, valid, deductive, inductive

- understanding arguments

- evaluating arguments

- deductive args (valid & sound)

- inductive args (if we get to them in class on Friday or Monday)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

logistics

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Friday, February 5, 2010

Homework #1

As I mentioned in class, our first homework assignment is to evaluate the arguments from #1 (a) through (h) on pages 187-188 of the textbook. The homework is due at the beginning of class on Wednesday, February 10th, and is worth 40 points (4% of your overall grade).

On an unrelated note, I found the reason the internet exists: hipster puppies.

On an unrelated note, I found the reason the internet exists: hipster puppies.

Monday, February 1, 2010

Defining Our Terms

1. Tool: I suggest watching Tool Academy to see our heroes in action:

2. Fugly: uh, rather ugly. Moe Szyslak has been called a few variations of this term.

2. Fugly: uh, rather ugly. Moe Szyslak has been called a few variations of this term.

3. Hipster: Urban Dictionary's entry is OK, but I like Wikipedia's entry on this term. If you want to find/become a hipster, try this helpful handbook, or this picture of the evolution of the hipster.

2. Fugly: uh, rather ugly. Moe Szyslak has been called a few variations of this term.

2. Fugly: uh, rather ugly. Moe Szyslak has been called a few variations of this term.3. Hipster: Urban Dictionary's entry is OK, but I like Wikipedia's entry on this term. If you want to find/become a hipster, try this helpful handbook, or this picture of the evolution of the hipster.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)